Viola Liuzzo was described by her

husband as someone “who fought for everyone’s rights. She was a champion for

the underdog.” Liuzzo had come to Selma to help marchers in any way she could.

She had told her husband, “its everyone’s fight,” the evening she left to drive

to Alabama to help protesters in the Selma to Montogomery March.

Liuzzo grew up in segregated Tennessee, and this formed her views on civil rights. An active member of the

Detroit chapter of the NAACP, she was familiar with organized protests and the

problems in Alabama. She had left Detroit after witnessing the events of “Bloody

Sunday,” on March 7th, when police and vigilantes attacked Black

marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge to stop them from marching to Montogomery to

protest their inability to vote due to poll taxes and poll tests.

On March 25th, the protest

had climaxed, and demonstrators were breaking up in too small groups and

looking for ways home. Liuzzo agreed to shuttle people back to Selma and was

riding with a young Black man, 19-year-old Leroy Moton. He had agreed to help

drive if she needed it. After dropping some people in Selma Liuzzo and Moton

were headed back to Montgomery on State Highway 80 when they picked up a tail.

Earlier in the day, Ku Klux Klan

members had gathered at Silver Moon Café. They had been keeping the protest under

surveillance under orders from their Klavern in Birmingham. When they left

Selma to head back to Montgomery, they saw Liuzzo’s green Oldsmobile. The car

had Michigan plates, and Moton was sitting in the front seat with Liuzzo. This triggered

them because it was everything they hated about the civil rights movement,

outsiders, and race mixing. So, they followed. Moton said that Liuzzo was

singing “WE Shall Overcome” when the car caught them, even though they were

going down the two-lane road at nearly 100 miles an hour. Even at the speed, the

Klansmen pulled alongside and shot into the car, instantly killing Liuzzo, the

car wrecked knocking Moton out. When he woke up, he flagged down a passing

truck and notified the authorities in Selma.

Within 24 hours, President Lyndon

Johnson had appeared on television to report the arrest of three Klan members

for Liuzzo’s murder. Eugene Thomas, Collie Leroy Wilkins, Jr., and William

Orville Eaton had all been arrested. A fourth man, Gary Rowe, had not been since

he was an FBI informant.

Rowe went on to testify against

the men in three trials. Although he had been recruited to infiltrate the Klan

in 1959, he was also being recruited by the Klan, in his time as an informant

Rowe hade been under superstition many times including for providing the

dynamite or even that he built the bombs that killed four little girls in the

1963 the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham. Rowe, though, was protected by the FBI on orders from director J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover

took the civil rights movement and protests personally and felt certain that Dr.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a communist agent trained to disrupt America. Hoover

was concerned that the high-profile murder could lead the press to find out

about Rowe, and that would make the FBI culpable in not just the murder of Liuzzo

but other activities.

Liuzzo’s body was flown back to

Detroit on the private plane of Teamster’s president, Jimmy Hoffa, and met by her

family. Liuzzo’s husband was a business manager for the Teamsters in Detroit at

the time of the murder. The funeral was held on March 30th at the

Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic Church in Detroit. It was attended by

Dr. King, future congressman John Lewis, and NAACP executive director Roy

Wilkins. Also, by Michigan Lt. Governor William G. Milliken. Hoffa and United

Auto Workers Union President Walter Reuther.

Despite the high-profile

individuals at the funeral or perhaps because of it, crosses were burned the

next night in Detroit, including on the Liuzzo’s lawn. For at least the next

two years, the family had security at their home both extended police presence

and private security. Despite this, the Liuzzo children were bullied and

taunted at school.

This was made worse as trial preparations

began, and the Klan, the lawyer for the three accused men, and the FBI all seemed

to work in tandem to smear Liuzzo’s reputation. Rumors and stories were spread

that Mrs. Liuzzo had been a heroin user and had abandoned her family to have

sexual relations with Black men.

At the state trials, these rumors

and the bias present in the jury resulted in a hung jury in the accused's first

trial after just 6 hours. A second trial led to a verdict of innocent by an all-White

male jury. If left at that level, there would be no justice. Fortunately, President

Johnson’s Department of Justice decided to bring federal charges against the

three Klan members for conspiring to violate the civil rights of Mrs. Liuzzo.

They were convicted and each sentenced to 10 years in prison.

The murder of Viola Liuzzo became

a transcendent moment in the Civil Rights cause. She became a martyr for the movement,

and it was her murder that led Johnson to declare war on the Klan and bring

Hoover to heel by ordering the director to engage in enforcing the Civil Rights

Act. It is also believed by most historians that Liuzzo’s murder was the push

to get the Civil Rights Act passed.

In the aftermath of the murder Leroy

Moton became an agitator and hard worker for the NAACP and Southern Christian

Leadership Council to help to register voters in Illinois, Michigan, and

Georgia. In interviews, he said that for years he had guilt and wondered why he survived

when a mother of 5 didn’t. He died quietly at age 78 in 2023 at his son’s home

in Hartford, Connecticut.

Rowe would become a highly

controversial figure for the rest of his life. He was subpoenaed to appear before a

Congressional Committee. He was prepared to make the FBI the wrongdoers in his

life and testified that they never attempted to stop his violence against

Blacks. He received immunity and went into the witness protection program even

though he acknowledged attacking freedom riders and killing a Black man. He

wrote a book about his time undercover that was turned into a TV Movie in 1979.

The Liuzzo family sued the FBI

for the death of Liuzzo and associated damages. On May 27, 1983, Judge Charles

Wycliffe Joiner rejected the claims, saying there was "no evidence

the FBI was in any type of joint venture with Rowe or conspiracy against Mrs.

Liuzzo.”

In the decades since Mary Liuzzo

Lilleboe, her brother Anthony and sister Sally have taken every opportunity to

tell the world of the heroism and compassion of their mother, as well as the

pain experienced by their family following her death and the subsequent smear

campaign against her character. They have dedicated their lives to destroying

the image Hoover had tried to create.

|

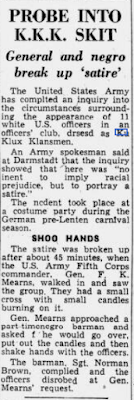

| Leroy Moton in 1965 and 2023 |

Sources:

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1965/03/27/101535542.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

https://www.wvtm13.com/article/alabama-montgomery-selma-viola-liuzzo-kkk-civil-rights/63907002

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/liuzzo-viola-0

https://www.learningforjustice.org/classroom-resources/texts/viola-liuzzo

https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/local/selma50/2015/03/08/liuzzos-children-know-played-pivotal-role/24631939/